Do you ever have trouble getting your living room temperature just right? It gets cold outside, so you bump the heat up. Whoops, too much, now you’re too hot. Down with the thermostat. Wait, now it’s freezing, turn up the heat! Cycle after cycle, until finally you get it dialed in just right. Now you can fire up the TV and binge-watch your favorite show.

Congratulations, you understand systems thinking – that’s it in a nutshell.

Unfortunately, most of the human systems we deal with are not so easily understood, let alone adjusted. We also deal with systems that suffer from discontinuous change – nudge a bit, change a bit, nudge a bit, change a bit, nudge a bit, the whole thing falls off a cliff. That can be pretty hard to manage, because you’re never sure just which nudge is going to cause massive change.

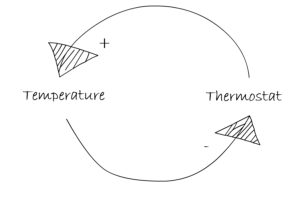

One reason many change efforts are ineffective is that they address only symptoms of an issue, rather than the issue itself. To combat this, it’s helpful to use systems diagrams to better understand how an entire system works before you start to tinker with the parts of the system. A particularly helpful type of system diagram is the causal loop diagram. To create a causal loop diagram, you must identify the variables that are at work in a system. Going back to our heating example, what are the variables? It’s a fairly simple system, so we can identify two variables – the temperature in the room, and the setting on the thermostat. Once you’ve identified the variables in the system, you need to identify the linkages between the variables. Again, in a fairly simple system there aren’t a lot of linkages. Below is the causal loop diagram for our heating problem.

You can see the thermostat links directly to the temperature, and vice versa. You can also see we’ve added a “+” and “-” sign to the diagram. This is the other key to causal loop diagrams – we have to identify what happens to other variables when we act on one variable. In this case, if we adjust the thermostat up, it will cause the temperature in the room to go up. If we adjust the thermostat down, it will cause the temperature to go down. This is a positive causal link, meaning that a change in the thermostat will cause a change in temperature of the same direction. On the temperature -> thermostat link, you can see we’ve added a “-” sign. If we turn the thermostat up, the temperature will go up. When the temperature goes up, it will cause the thermostat to read a higher temperature, and then disengage the furnace. Thus, we can call that link a negative causal link – an action on one variable causes an opposite reaction on the linked variable. (Note, some causal loop diagrams will use “S” instead of “+”, for a “same direction” relationship, and an “O” rather than “-“, for an “opposite direction” relationship.)

The relationship between variables is the critical piece of information we want to identify before we act on a system. In our thermostat example, we have one positive relationship, and one negative relationship. This creates a balanced system – as long as the thermostat and the furnace are working, this system will achieve and maintain the temperature we request. A reinforcing loop, on the other hand, has an even number of negative links, which allows the positive links to constantly increase (or decrease) the results of change. Think of it like a viral online video – you share a video with 10 friends, they each like it and share it with their friends, and on and on until we’re all sick of hearing and seeing this video. However, if we want to change a system, we need to find leverage points that will allow us to reinforce or reduce certain behaviors within the system.

As you can imagine, few systems we deal with are as simple as our example here. Any system that includes even a handful of processes and two or three human beings is going to be a complex web of relationships. Check out the causal loop diagram Wikipedia page for a doozy of a diagram. The trick to using systems diagrams effectively is to figure out how much of the system you need to document, making sure you identify the critical variables for the change you’re considering, and being as certain as you can about the relationships between those variables. Once you have those key pieces of information, you can start to think about what kind of change you need to implement for the result you’re seeking.

Need help figuring out your system? Check out the resources below, and if you have any questions don’t hesitate to get in touch!

Additional Reading

- Thinking in Systems: A Primer by Donella Meadows is a great brief introduction to systems thinking.

- The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization by Peter Senge is a classic business bestseller that discusses systems thinking in the context of building a learning organization. If you work in a company or organization today, you should read this book.

- Systems Thinking Basics: From Concepts to Causal Loops by Virginia Anderson and Lauren Johnson is a great primer on using causal loop diagrams to explore the leverage points within a system. It’s also got a lot of great exercises to help you practice.